Murder in Space

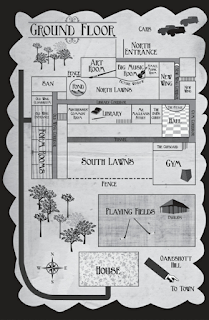

In his introduction to Spatiality, Robert T. Tally Jr. suggests that literature works as a kind of mapping, "offering its readers descriptions of places, situating them in a kind of imaginary space, and providing points of reference by which they can orient themselves" (2). He goes on to point out that the opposite is also true, that "to draw a map is also to tell a story" (4). This week I'm thinking about how these two things, the story-as-map and the map-as-story play out in a series of detective novels that I've really enjoyed.

In a recent talk during a book launch (for Death Sets Sail, which I’ll discuss

later) the author Robin Stevens described travelling to Egypt, the

setting of the book, and taking copious notes on such matters as the exact position of the sun at particular points in the day, in relation to a ship

heading South on the Nile, as these could all affect the events of the plot.

Stevens writes children’s murder mysteries, which are heavily inspired by the

golden age crime fiction of authors like Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh and

Dorothy Sayers. In the mystery story, a sense of how the space works, and what

the characters’ relationship with it is, is necessary in order that the reader

have a sense of what is possible. This is crucial in a genre whose appeal is

partly based on the fact that it’s a shared game; the reader (as long as Fair Play is being observed) has access to all that they need to solve the crime,

and quite often is in competition with the fictional detective to see who gets

there first.

In a recent talk during a book launch (for Death Sets Sail, which I’ll discuss

later) the author Robin Stevens described travelling to Egypt, the

setting of the book, and taking copious notes on such matters as the exact position of the sun at particular points in the day, in relation to a ship

heading South on the Nile, as these could all affect the events of the plot.

Stevens writes children’s murder mysteries, which are heavily inspired by the

golden age crime fiction of authors like Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh and

Dorothy Sayers. In the mystery story, a sense of how the space works, and what

the characters’ relationship with it is, is necessary in order that the reader

have a sense of what is possible. This is crucial in a genre whose appeal is

partly based on the fact that it’s a shared game; the reader (as long as Fair Play is being observed) has access to all that they need to solve the crime,

and quite often is in competition with the fictional detective to see who gets

there first.

As Kristel Autencio demonstrates in this BookRiot post, many

writers in the classic mystery genre use maps and floor plans to help the

reader visualise the possibilities and challenge them to come up with a

solution. I’m interested in how Stevens uses maps and

floorplans differently in different settings to aid the reader in following the

crime through space.

First Class Murder (2015) is set on a train, and begins with plans of the sleeper and dining cars. This book is a partial tribute to Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express (1934), and its plan of the sleeping car is quite similar to the one used by Christie (included in Autencio’s post, linked above): the layout simply lists the locations of the passengers and leaves it up to the reader to work out how each of them might have accessed the berth where the murder victim was sleeping. But more important than the space are the people—the floorplan acts to circumscribe (quite literally) our list of suspects. In the real world it might be possible for a complete stranger to sneak in, commit the crime and leave, but the fair play conventions of the genre, and the “map” itself, both impose a kind of order and regularity on the world of the story. The reader is reassured that this is all there is; we have access to all the information we need; nothing beyond the edges of the map needs to exist. We’re in control of the space.

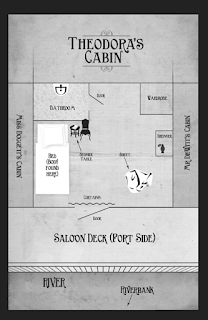

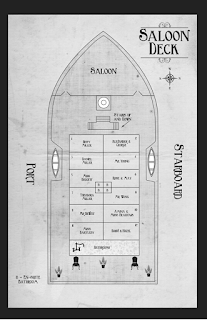

Which brings us to Death Sets Sail, published earlier this month. Modelled partly after Christie’s Death on the Nile (1937), this book is set on a cruise along the river Nile. The reader is given two depictions of the space; a general plan of of the cabins on the saloon deck, and a plan of the victim's room after the murder has been committed.

Comments

Post a Comment