Portal fantasies and anticolonial uprisings

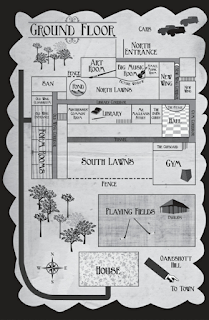

C.S. Lewis's Chronicles of Narnia books are perhaps the most recognisable portal fantasies there are-- The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950) is the first book Farah Mendlesohn mentions when she explains the concept of the portal fantasy in Rhetorics of Fantasy , and I've found that I tend to default to that example as well when I try to explain the genre. It's also my default example when I try to talk about my research into spatiality in children's fantasy after empire. Because apart from being portal fantasies, the Narnia books are deeply rooted in ideas of colonialism and portrayals (both positive and negative) of colonizers. In the first book, published three years after the loss of British India and the independence of India and Pakistan, a group of British schoolchildren travel to a foreign land, discover that the natives are desperate for them to rule them, due to their unique racial background (they are human), and depose and replace the existing tyrant...